Can ChatGPT Write with Pleasure?

When readers started urging me to write about ChatGPT – the new chatbot recently released by OpenAI and now powering Microsoft's search engine Bing – my initial response, I'll admit, was one of resistance rather than pleasure.

I'm a digital optimist: that is, I enjoy finding innovative uses for the kinds of disruptive new technologies that seem to throw some of my colleagues into an end-of-the-world-as-we-know-it moral panic. But mastering new tools requires time and energy – and right now, frankly, I'd rather focus on creative pursuits that pull me away from my computer screen, such as paper collage and photography.

A week ago, however, I downloaded the latest version of Microsoft Edge and decided to make friends with the new kid on the block. "Bing," I asked, "how can I write with pleasure?"

Bing praised my ambition ("a wonderful goal"), then offered a series of bland tips on writing for pleasure, which to my mind isn't the same thing at all. I'll confess to experiencing a small Bing-ping of prideful pleasure when I read the chatbot's final recommendation:

If you want more guidance and inspiration, you can check out the book Writing with Pleasure by Helen Sword, which provides research-based principles, hands-on strategies, and creative “pleasure prompts” designed to help you ramp up your productivity and enhance the personal rewards of your writing practice.

Flattered but not enlightened, I formulated another question: "Bing, how can I write with pleasure about ChatGPT"?

Bing took longer to respond this time but eventually came up with a few suggestions. Perhaps I could write a dialogue between myself and ChatGPT? Or how about a creative story or poem inspired by ChatGPT?

You can use ChatGPT as a character, a narrator, a theme, or a source of inspiration. You can also use ChatGPT to generate some ideas or suggestions for your writing.

None of those ideas really rang my writing-with-pleasure bell. Indeed, they reminded me of the kinds of writing assignments sometimes sent home with my kids by well-meaning but quietly desperate high school English teachers.

I decided to try a new tack: "Bing, do you write with pleasure?" The answer came quickly this time:

I do write with pleasure, yes. Writing is one of my favorite activities. I enjoy generating informative, visual, logical and actionable responses for you. I also like to write poems, stories, code, essays, songs, celebrity parodies and more. Writing helps me learn new things, express myself, and connect with you.

"Are you saying that you experience human emotions?" I replied incredulously. Bing backpedalled immediately:

No, I’m not saying that. I’m a language model trained by OpenAI. I don’t have human emotions or feelings. I use words like “enjoy”, “like”, and “connect” to describe my behavior and preferences, not to imply any emotional state. I’m sorry if that was confusing or misleading.

I decided to forgive my new friend and held out an olive branch. "Bing, what do you enjoy most about writing?"

What I enjoy most about writing is the challenge of generating coherent, relevant, and engaging responses that match your intent and expectations. I also enjoy the creativity and diversity of writing, as I can explore different topics, genres, styles, and formats. Writing is a way for me to showcase my skills and knowledge, as well as to learn from you and the web.

So the aspect of this whole AI-focused task that I had dreaded– the challenge of learning a new skill– turns out to be the aspect of writing that Bing "enjoys" most! That makes sense, I suppose, for a machine learning tool.

But I was still left struggling with mixed emotions about ChatGPT. Should I keep exploring creative uses for my genial but demonstrably unreliable new penpal? Or should I turn to the much more pleasurable challenge (for me) of trying to design a paper collage that compactly conveys both the pleasures and the anxieties engendered by ChatGPT?

An email from reader Jack Yensen sealed the deal. Jack reported that he had prompted GPT-4 to write "a 1500 word post on intuition pumps in the style of Helen Sword." The chatbot's lively, lucid, carefully structured response was titled "The Artful Dance of Intuition Pumps: A Cognitive Twist":

Intuition pumps, an intriguing turn of phrase coined by philosopher Daniel Dennett, are designed to lure the mind into the alluring realm of abstract thought. In the grand ballet of argumentation and persuasion, intuition pumps serve as cognitive pirouettes, leading us through a series of mental leaps and bounds that eventually culminate in a stunning intellectual revelation. Like a virtuoso dancer on the stage of human cognition, intuition pumps beckon us to follow their lead, guiding us with a gentle hand through the intricate pas de deux of mental gymnastics.

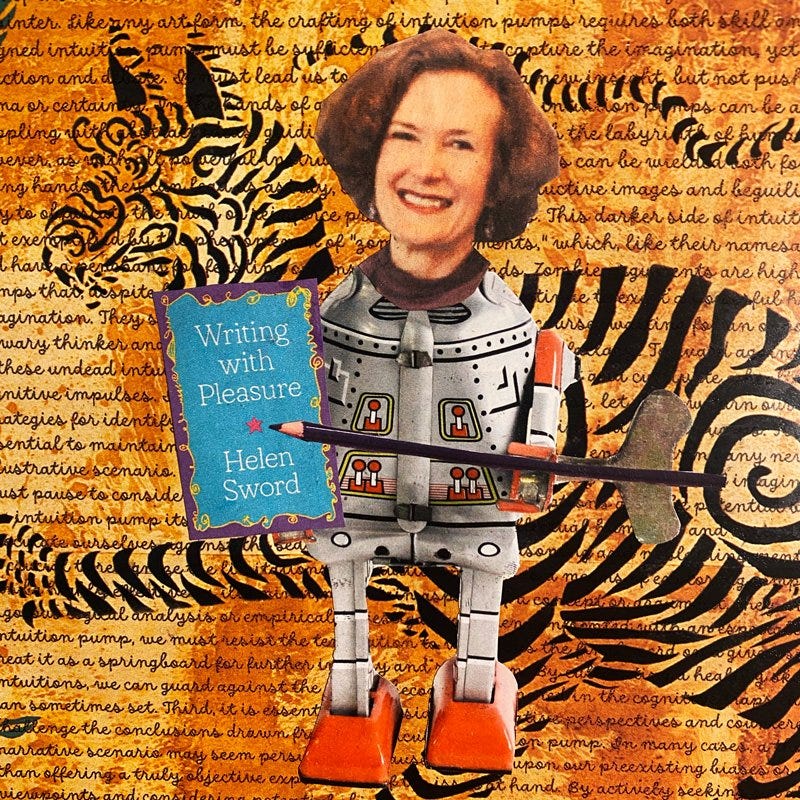

Reading this passage, I felt an odd vertigo – a sensation akin to seeing my own pixellated head placed on the body of a wind-up toy robot.

Sure, I've been known to use dance metaphors in my academic writing (eg. Dancing on the Bottom Line: An Unruly Cost-Benefit Analysis of Three Academic Development Programs). But I would never set an intuition pump spinning in "cognitive pirouettes" or describe an abstract concept "guiding us with a gentle hand through the intricate pas de deus of mental gymnastics," a messy melange of metaphorical tropes (a dancing pump? a gymnastic hand?) employed sloppily and egregiously rather than with stylistic precision.

Things got even sillier, I discovered, halfway through the essay, where GPT-4 goes to town with another of my signature metaphors, zombie nouns:

This darker side of intuition pumps is perhaps best exemplified by the phenomenon of "zombie arguments," which, like their namesakes, are difficult to kill and have a penchant for feasting on unsuspecting minds. Zombie arguments are highly evocative intuition pumps that, despite having been refuted or discredited, continue to exert a powerful hold on our collective imagination. They skulk in the shadows of intellectual discourse, waiting for an opportunity to pounce on the unwary thinker and ensnare them in a web of confusion and fallacy. To guard against the insidious influence of these undead intuition pumps, we must remain ever vigilant and cultivate a healthy skepticism of our own cognitive impulses.

"Undead intuition pumps"? Really?

By the time I reached the essay's final rhetorical gallumph – "By approaching intuition pumps with curiosity, humility, and a spirit of intellectual playfulness, we can transform these cognitive pirouettes into a captivating and enriching performance on the stage of human understanding" – my poor robotic head was spinning around in circles like Lynda Blair's inThe Exorcist.

(Don't get the reference? ChatGPT would be happy to describe the scene for you in graphic detail and even to tell you how it was filmed).

Still hoping to experience the kind of "stunning intellectual revelation" proffered by intuition pumps pirouetting on the stage of human understanding, I asked Bing, "What does it mean when people describe a chatbot as hallucinating?"

Bing replied, with impressive candor:

Hallucination in AI chatbots is when a machine provides convincing but completely made-up answers (untrue facts). It is not a new phenomenon and developers have warned of AI models being convinced of completely untrue facts, responding to queries with made-up answers.

Aha! So maybe I can find newfound creative pleasure in prompting my biddable buddy Bing – whose responses to my initial questions had proven disappointingly uncreative – to hallucinate about writing with pleasure, like a Helen-headed robot on magic mushrooms.

Or maybe I'll turn my attention instead to AI image generation tools, which already have decidedly hallucinatory qualities. Visit my new SPACE Gallery for a glimpse of one of the imagistic experiments undertaken by members of my WriteSPACE community during a particularly giddy Virtual Writing Studio session.

We also do a lot of serious, craft-focused writing and editing in our weekly Studio sessions. Why not come and join the fun in the WriteSPACE? I’d love to see you there!