Rēinga by Helen Sword (video screencast and voiceover recorded on March 5, 2024)

Dear fellow writer,

Over the years, I’ve written a lot about writing and risktaking: for example here and here and here. All writing is risky, after all — and as a scholar, mentor, and tireless advocate of stylish academic writing, I see it as my mission to empower writers to face those risks with courage, resilience, and even joy.

Rēinga is a hypermedia poem about creative risktaking that enacts and embodies creative risktaking. Cape Rēinga is the place in the far north of Aotearoa New Zealand where, according to Māori legend, the souls of the dead leap down the roots of an old pōhutukawa tree and start their journey to their ancestral homeland of Hawaiiki. Rēinga variously signifies “the place of leaping,” “the departing place of spirits,” or “the netherworld,” the place where the spirits go.

First published in March 2009 in ka mate ka ora: a new zealand journal of poetry and poetics, Rēinga exists in three different versions in my online poetry collection The Stoneflower Path (2007-2009): as a hypermedia digital poem; as a plain text linear poem; and as an audio recording.

Rēinga by Helen Sword (voice recording from 2009)

The poem at the top of this post, recorded in March 2024, is clearly different from the one that I recorded back in 2009, not only in terms of my reading pace (slower) and the timbre of my voice (older), but because the words are different. That’s because neither of these recordings fully captures the complexity of the “real” hypermedia poem, which exists in potentially millions of versions.

Do you find the prospect of leaping into a bottomless poem discomforting? Exhausting? Exhilarating? I suspect that your answer to that question will tell you something about your own propensity to take creative risks — or not. Either way, I hope that my guided tour into and through the labyrinthine roots of Rēinga will inspire you to try something new, maybe even something risky, in your own writing.

Enjoy!

The Stoneflower Path

Fifteen years after I first planted The Stoneflower Path in cyberspace, the whizzy website of which I was once so proud now looks as clunky and dated as Bill Clinton’s Blackberry. That’s the risk, I guess, of creating at the cutting edge (or, in my case, at the colorful edge) of technology: everything ages so quickly. An even greater risk, I secretly suspected at the time, was irrelevance. I put in many hours creating those two dozen digital poems using Dreamweaver, Photoshop, Audacity, and Flash; but was anyone ever going to read them, engage with them, remember then? Much as I feared, my self-published collection attracted little critical attention and slowly faded into obsolescence. (Only recently has the tide turned; a few months ago I learned that The Stoneflower Path is now considered a digital literary landmark!)

My hypermedia collection deliberately spotlights the risks and rewards of hypertext, the literary genre that The Stoneflower Path at once embodies, critiques, and celebrates. A hypertext is any text that contains hyperlinks: that is, digital links to words, images, or other media in or beyond the text.1 Hyperlinks offer readers a convenient way of accessing information related to what they’re reading, which is why they’ve become such a familiar presence in virtually every text designed to be read online (including this one). But those temptingly highlighted links risk disrupting the linear flow of our reading and directing our attention elsewhere, much as a footnote drags our eyes to the bottom of the printed page.

When planted deliberately to confuse or misdirect, hyperlinks can lead us off the beaten track completely, sending us spinning into a textual maze with no clearly marked exit. That’s how Rēinga works — and that’s why reading the full hypermedia version of the poem requires a willingness to leap into the dark.

At the place of leaping

First conceived of and published before smartphones and touchscreens became ubiquitous, Rēinga is best experienced on your desktop computer or laptop using a mouse or trackpad.

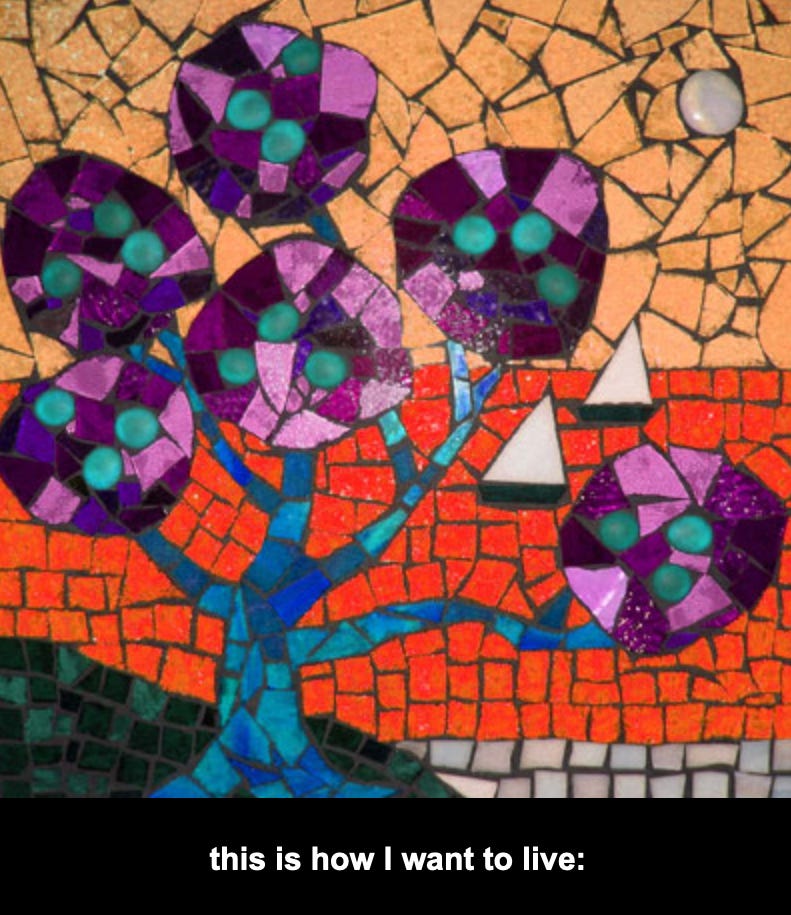

When you enter the poem by clicking on the title, you’ll always be directed to the same static image — a stained glass mosaic depicting a pōhutukawa tree, two sailboats, and a full moon — and the same opening line:

At the place of leaping

From there, however, the poem bifurcates. As you move your mouse around over the tree, the land, the sea, and the sky, you’ll discover two live hyperlinks. This is your first moment of uncertainty, your first leap into the unknown. A click on the lower sailboat takes you to a glowing purple-and-orange image with the line, This is how I want to live:

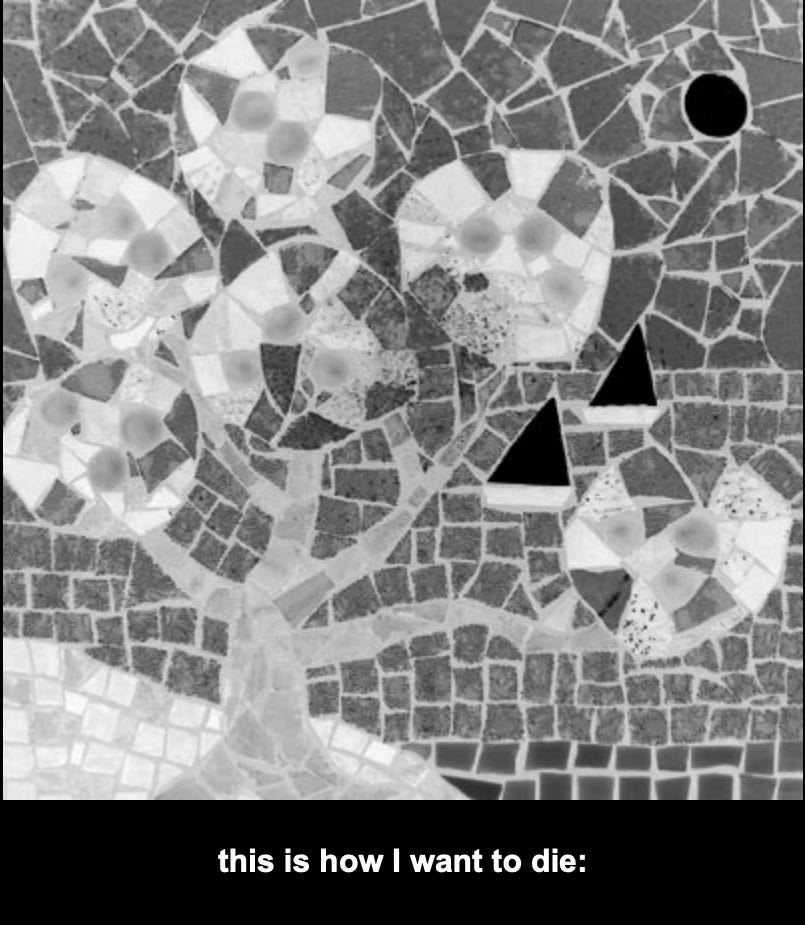

A click on the upper sailboat takes you to a grayscale image with the line, This is how I want to die:

From there, it’s no longer a matter of leaping off the cliff into life or death so much as swimming in a roiling sea of possibilities. With 20 live hyperlinks per screen (18 pōhutukawa blossoms + 2 sailboats + 1 moon, minus the current link) leading to more than 50 possible image-plus-line combinations (I used every single Photoshop filter!), you can often create a poem of 20 lines, 30 lines, or more without encountering a single repeated line.

The moon delivers only moon-related phrases, and the sailboats always bring you back to the same two choices — this is how I want to live, this is how I want to die — so you can use those three objects to create some structure for your wanderings. For example, to generate a 16-line poem with a similar cadence to my two voice recordings, try the following sequence of clicks:

at the place of leaping

[upper sailboat] this is how I want to die:

[blossom]

[moon][lower sailboat] this is how I want to live:

[blossom]

[moon]

[blossom][upper sailboat] this is how I want to die:

[blossom]

[moon]

[blossom][blossom]

[blossom]

[upper sailboat] this is how I want to die:

[lower sailboat] this is how I want to live:

Then return to the place of leaping (either by using your back button or by closing your browser window) and repeat the sequence without making any effort to follow exactly the same path. You’ll end up with a new poem that sounds and feels similar to the first, yet hauntingly different.

The hypertext of life

Life is a hypertext, full of risky leaps into the unknown. So is writing. So is art — or, for that matter, any form of creative practice.

In a post titled RISK, our #AcWriMoments prompt for the month of March 2024,

and I each recalled a risk that we’ve taken in our own professional lives. I reflected on how, back in 2001, my husband and I decided to move from our comfortable home in the Midwestern United States to a small island nation in the South Pacific with our three kids, all our earthly possessions, and no jobs or likely job prospects in the academic fields we had left behind:Those first few years were tough, as we struggled to find our feet personally and professionally. But eventually we both reinvented ourselves in new careers that suited us even better than the ones we’d left behind, and our children got to grow up amongst friends and family in one of the most beautiful countries on earth, a place with strong social and community values that we cherish. Not long after we moved here, I experienced an unexpected creative flowering as a poet and artist, like a rose bush blooming more abundantly than ever after a hard pruning, and I shifted from writing about modernist poetry to writing about scholarly writing.

If, back in 2001, I had clicked on the hyperlink that said Stay rather than the one that said Leap, would I be writing this post today? I doubt it. The poems of The Stoneflower Path were among the many products of the creative flowering that I experienced within my first few years in Aotearoa New Zealand — and Rēinga remains one of my favorite blossoms in the bouquet. I still get a thrill from generating a new poem every time I click beyond the opening image, a photo of the stained glass pōhutukawa mosaic that I crafted “in real life” for my mother’s 80th birthday back in 2005. (It now resides on my brother’s mantelpiece in California). And I still love leaping into the unknown to find out what I’ll learn there.

We have to continually be jumping off cliffs and developing our wings on the way down. (Kurt Vonnegut)

Warm thanks to the many risktaking writers who inspired this post, especially

, , David Ciccoricco, and , whose question about risk first sent me back to reread Rēinga, and from whom I borrowed the Vonnegut quote.If you enjoyed reading this post, please share it with a friend, leave me a comment, and toss a heart off your own risky cliff into the WriteSPACE, the space of pleasurable writing that this newsletter cultivates and curates. Your feedback means so much to me.

Kia pai tō koutou rā (have a great day) – and keep on writing!

Helen

Write more, right now! Join fellow writers from 30+ countries in the WriteSPACE, the ultimate membership site for academic and professional writers who aim to lift their writing game. As a WriteSPACE member, you’ll get premium access to hundreds of online resources, diagnostic tools, and live events designed to help you sharpen your style, deepen your research impact, and coax your writing gently but firmly out the door. To try free for 30 days, click below and enter the discount code SNEAKPEEK.

Books on writing by Helen Sword

Writing with Pleasure

Princeton University Press, 2023

Air & Light & Time & Space: How Successful Academics Write

Harvard University Press, 2017

Stylish Academic Writing

Harvard University Press, 2012

The Writer’s Diet: A Guide to Fit Prose

University of Chicago Press, 2016

Hypermedia poetry, as digital pioneer Christopher Funkhouser explained in 1996, may also include “graphics, moving visual images, and soundfiles linked with (or instead of) printed text,” enabling “a variety of intertextual associations and graphical combinations” not possible in a conventional printed text. (It’s worth clicking on the link below to see the original html version of Funkhouser’s article; don’t you just love that vintage lime green font on a kelly green background?!) (Funkhouser 1996: “Toward a Literature Moving Outside Itself: The Beginnings of Hypermedia Poetry.”)